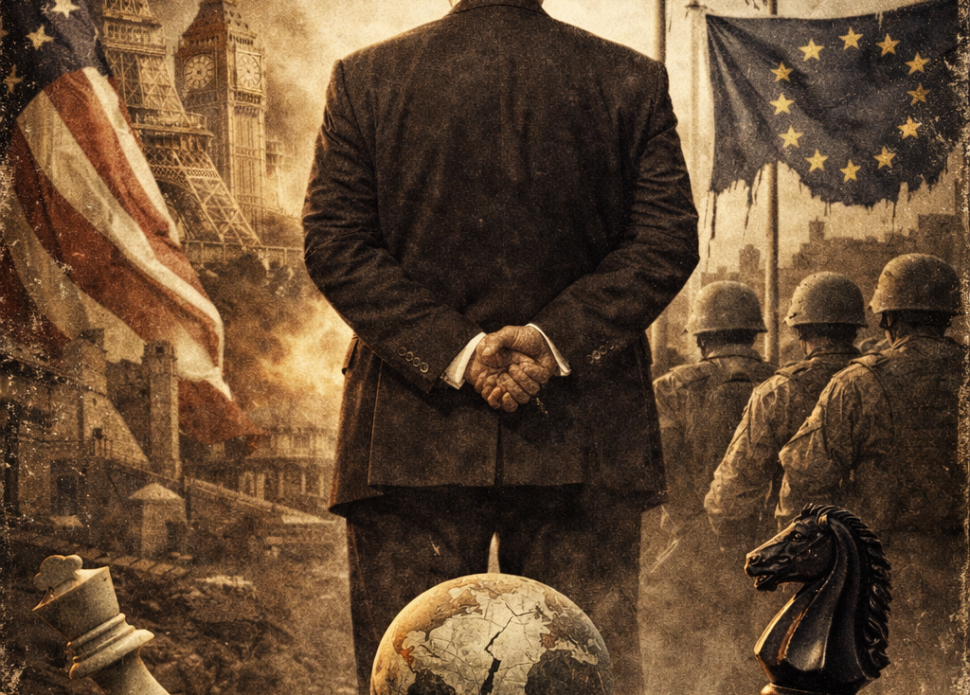

The United States has long been known for its firmness toward its adversaries; yet the historical experience of its allies suggests that defying Washington can, at times, entail costs exceeding those of opposing it outright. This paradox is encapsulated in a well-circulated dictum in the political literature: “It may be dangerous to be an enemy of the United States, but to be its ally can be fatal.”

This study proceeds from the premise that the management of allies has constituted a structural pillar of the American order since Washington’s transition from a phase of relative isolation—focused on consolidating its position within its immediate region—to a phase of global engagement and the construction of postwar arrangements. From this perspective, the study traces the intellectual roots of American strategic logic as the product of a foundational juxtaposition between the “republic” and the “empire.” It then turns to the critical moment of transition from isolation to leadership during the Second World War and the subsequent establishment of the American order, culminating in a contemporary question: does Trump’s approach represent merely a break in style, or does it amount to a more explicit—and perhaps more abrasive—return to the original foundations?

The Republic versus the Empire: The Intellectual Foundations of the American Order

On January 2, 1492, the Catholic Monarchs—King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile—completed the conquest of the Kingdom of Granada, the last Arab and Muslim polity on the Iberian Peninsula. In the context of that era, this conquest severed the final major political link between Muslims and Western Europe. Yet Europe’s search for alternative trade routes that would not pass through the lands of the “Mohammedans,” as Europeans commonly referred to Muslims at the time, remained a central dilemma for the continent’s kings and kingdoms. The most important commercial arteries—most notably the incense and spice routes from India and the Silk Road from China—ran through territories under Islamic rule, rendering control over these routes, or the ability to bypass them, a persistent strategic obsession.

At this moment of victory and consolidation, the Italian navigator Christopher Columbus found the long-sought opportunity to secure backing for a project he had advanced for years: crossing the Atlantic Ocean—on the premise of the earth’s sphericity—to reach India and Asia by sailing west rather than east. On October 12 of that same year, he reached the Caribbean, inaugurating a succession of voyages and explorations. In this context, the journeys of Amerigo Vespucci proved pivotal in consolidating Europe’s recognition that what had been reached was not “India,” as Columbus had believed, but an entirely new continent. From this recognition emerged the name “America,” bestowed in his honor, while the label “Indians” for the continent’s indigenous peoples endured as a vestige of the original misconception.

As religious conflict in Europe intensified amid the devastating wars between Catholics and Protestants—unleashed in the wake of the German monk Martin Luther’s objections, later canonized as the “Ninety-Five Theses”—this “New World” became a refuge for many subjected to religious persecution. In the political imagination, it also came to be cast as a putative bastion of freedom for those disillusioned with European monarchies and their recurring conflicts. On this basis, successive waves of settlement took shape in the New World, driven by European migrants—resentful and/or persecuted—seeking deliverance, liberty, and a decisive rupture with Europe’s bloody legacy. This foundational moment left a profound imprint on the American character and on its subsequent political model, an imprint that endures to the present day.

Within this historical–intellectual context, modern formulations of American doctrine do not appear detached from their original roots. In the new U.S. National Security Strategy issued in November 2025, specifically on the third page of the introduction under the heading “What Should the United States Seek?”, the opening statement reads: “Above all, we seek the continued survival and security of the United States as a sovereign, independent republic, whose government safeguards the natural rights endowed by God to its citizens and places their welfare and interests at the forefront of its priorities.” The phrase “natural rights endowed by God” may strike some readers as unusual, or seemingly at odds with the technical idiom typically associated with national security documents. Yet a return to American history suggests that this philosophy—grounded in the primacy of divine rights as broader than, and prior to, positive legal and constitutional rights—has been deeply embedded in the American political imagination since the nation’s earliest beginnings.

This conception is closely linked to what may be described as a “European complex” in the early American political imagination: a persistent sensitivity to the Old World model, perceived as synonymous with religious oppression, warfare, and monarchical conflict. This is evident in the writings and statements of early colonial leaders, who imbued migration to the “New World” with a religious character and framed it as a moral–spiritual exodus from Old World oppression. From the outset, biblical imagery—and the fusion of religion and politics—was central, as the Exodus narrative was invoked as a symbolic framework for interpreting the American experience. John Winthrop gave classic expression to this vision in his famous 1630 sermon when he declared, “We shall be as a city upon a hill; the eyes of all people are upon us,” casting America as a community bound by a distinctive moral covenant and placed under the gaze and scrutiny of the world.

In a similar vein, William Bradford described the settlers’ Atlantic crossing in explicitly religious terms, casting them as “pilgrims” who had left a land of oppression and lifted their eyes toward heaven, “their dearest country,” in imagery closely reminiscent of the Exodus and the crossing of the sea. By the early eighteenth century, Cotton Mather further entrenched this vision by portraying New England’s Puritan settlers as God’s chosen people who had established themselves in lands previously cast as “the devil’s territories”—a direct transposition of the idea of a new Israel in a promised land. This biblical imagination did not recede with America’s transformation into a nation-state. Rather, Herman Melville recast it in modern nationalist idiom when he wrote: “We Americans are the peculiar, chosen people—the Israel of our time; we bear the ark of the liberties of the world,” linking the American experience to a redemptive mission of universal scope.

This succession of interrelated visions reveals that the American republic was not conceived, in its self-image, merely as a political antithesis to imperial Europe, but as a moral–historical alternative to it—one that saw itself as a people emerging from a corrupt Old World into a new promise. Politically, the Founding Fathers sought to institutionalize this distinction by constructing an intellectual and constitutional project opposed to the European model, particularly its imperial form grounded in hereditary monarchies, permanent alliances, and recurrent wars. To this end, strict safeguards were established to prevent what was then described as the transmission of “European contagion” to the fledgling republic.

Thomas Paine articulated this view early on when he argued that Europe was “too thickly planted with kingdoms to be long at peace,” in contrast to an American horizon grounded in political union as a prerequisite for a stable republic. Accordingly, severing ties with the European world became a condition for building a new political order founded on liberty rather than expansion. In the same vein, Alexander Hamilton, in the opening essays of The Federalist Papers, framed the American experiment as a historical test of humanity’s capacity to establish good government based on “reflection and choice” rather than heredity and force—a direct counterpoint to the European imperial experience.

This awareness of the dangers inherent in the imperial model deepened with James Madison, who warned that war constituted the greatest enemy of public liberty, linking it to standing armies and the erosion of constitutional restraints—features he regarded as intrinsic to the European system of armed rivalry and balance-of-power politics. Thomas Jefferson, for his part, crystallized this republican principle in a clear political formula when he called for “peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations—entangling alliances with none,” thereby laying the foundation for economic openness without immersion in the logic of imperial domination and permanent alliances.

This vision reached its apex in George Washington’s Farewell Address, in which he emphasized that the cardinal rule in relations with foreign states was to “have with them as little political connection as possible”—an explicit rejection of the European system of permanent alliances and interlocking wars. Similarly, John Adams cautioned against the degeneration of republics into “corrupt modes of government when the constitutional balance is lost,” offering an implicit critique of European trajectories in which democracies or republics ultimately devolved into expansionist empires.

Accordingly, the American republic was not constructed as the natural heir to Europe, but as its conscious antithesis: a republic versus an empire, law versus lineage, commerce versus colonialism. Yet this foundational tension would later reemerge in a more complex form as the United States moved from the phase of model-building to that of system management, and from the discourse of republican exceptionalism to the demands of leadership in a post–great-power war world.

From Isolation to Leadership: World War II and the Making of the American Order

The United States underwent four principal phases before its emergence onto the global stage—or, more precisely, before that emergence was summoned in a manner that proclaimed it a leading power within the international system. The first phase began on July 4, 1776, with the Continental Congress’s declaration that the thirteen American colonies had become independent states, severing their ties with the British Empire. The second phase took shape with the proclamation of the Monroe Doctrine during the presidency of the fifth U.S. president, James Monroe, on December 2, 1823, aimed at securing the American sphere of influence and insulating the New World from European conflicts, a significant portion of which were then being fought in the southern part of the American continent. The third phase emerged with the consolidation of internal unity and the suppression of secessionist movements through the defeat of the Confederate states and the conclusion of the Civil War in 1865 in favor of the Union. The fourth phase consisted in completing the process of incorporating additional states into the Union, which numbered thirty-six states on the eve of the Civil War’s end—a process carried out largely through purchase agreements, contractual arrangements, or limited-scale wars.

Throughout these phases, the United States adhered to the compact laid down by the Founding Fathers, refraining from involvement in international politics—particularly European affairs. This choice was not driven solely by ideological considerations; it was also grounded in concrete geographic and security realities. The United States effectively inhabited a “New World,” separated from the Asian and European Old World—with its complexities, conflicts, and wars—by two vast oceans: the Atlantic to the east and the Pacific to the west. There was no genuine security concern that those conflicts would spill onto American territory or pose a direct threat to U.S. national security. Within its regional environment, the United States expanded territorially, annexing lands it deemed strategically valuable, securing its southern flank by isolating the New World from Europe through the Monroe Doctrine, while maintaining to the north a relationship of stability and friendship with Canada—and, by extension, Great Britain—in the post-independence era.

As a result, U.S. relations with Europe were largely confined to trade and economic exchange, without political intervention or involvement in European conflicts—except during the First World War. Even then, Washington did not enter the war until three years after declaring neutrality, doing so on April 6, 1917, in response to a series of cumulative developments. In January 1917, British intelligence revealed a secret German telegram from Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann to Mexico, proposing an alliance against the United States in exchange for the recovery of territories Mexico had previously lost—Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. In addition, American commerce with Europe had been severely affected by German submarine attacks on U.S. military and civilian vessels in the Atlantic, most notably the sinking of the RMS Lusitania in 1915, which resulted in the deaths of 128 American citizens. These developments were compounded by the failure of all American efforts to resolve the crisis with Germany peacefully, owing to Berlin’s intransigence.

Following this initial experience, the United States sought to establish new foundations for peace and international law. Although the twenty-eighth U.S. president, Woodrow Wilson, participated in the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 and contributed to the drafting of the Treaty of Versailles, he accepted the treaty reluctantly, objecting to several of its provisions—particularly those that entailed the humiliation of Germany and were insisted upon by Britain and France. Wilson believed such terms would not lay the groundwork for a just peace and could pave the way for another war—a prediction that would later prove accurate. He also encountered firm resistance from the two European powers to his Fourteen Points, foremost among them the principle of self-determination for colonies. Nevertheless, he agreed to the treaty because it incorporated the project of the League of Nations, which he envisioned as an unprecedented collective framework to preserve peace and prevent future wars. Notably, however, the U.S. Senate rejected ratification of the treaty twice, in 1919 and 1920, out of concern that League membership would constrain American sovereignty and entangle the United States in future European wars absent an independent national decision.

After this experience, Washington concluded that its limited engagement in European affairs had failed to achieve the desired objective of halting the continent’s bloodshed, and that Britain and France were unwilling to cooperate meaningfully in establishing a new global order. The United States therefore reverted to a policy of relative retrenchment, focusing on economic and commercial activity and on addressing the effects of the Great Depression, which struck its economy between 1929 and 1939. As recovery began, the Second World War erupted in Europe. Although a limited set of domestic voices advocated U.S. participation, these calls encountered strong opposition—most prominently from the famed American aviator Charles Lindbergh, who founded the “America First” Committee on September 4, 1940, grounded in an ideology of non-intervention and the avoidance of foreign—especially military—alliances.

The United States entered the Second World War following Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941—marking a second instance in which American intervention came as a direct response to an external assault. From that moment onward, Washington recognized that isolation was no longer a viable policy. At the same time, it resolved not to repeat the failures that had followed the First World War. Accordingly, it chose to link its intervention to the establishment of comprehensive rules for a new global order, grounded in peace, legal structures, and the prevention—or at least the mitigation—of war.

The Tehran Conference, convened on December 28, 1943, among the leaders of the United States, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain, constituted the first building block of this order. At Tehran, Washington assumed leadership of military planning for the opening of the Western Front and began deliberations over the future of Europe and Japan. The Yalta Conference followed, held between February 4 and 11, 1945, to determine Germany’s fate, lay the foundations of the new international system in line with American conceptions, and divide spheres of influence among the victorious powers. President Franklin D. Roosevelt acceded to certain demands advanced by Joseph Stalin, based on calculated considerations aimed at creating a balance that would prevent the recurrence of war and subject recalcitrant European powers—chiefly Britain and France—to the pressures of the new order. Final arrangements were then completed at the Potsdam Conference, held between July 17 and August 2, 1945, under the leadership of the new U.S. president, Harry Truman.

These arrangements culminated in the entry into force of the United Nations Charter on October 24, 1945, with the United States designated as the organization’s permanent host and exercising clear dominance over its institutions. Soviet control was consolidated over the three Baltic states—Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia—as well as over western regions of Ukraine; a communist regime was established in Poland; and Germany was divided into two parts. Through this configuration, the United States broke the British–French grip over Europe, neutralized the German threat, undertook the rehabilitation of West Germany, and simultaneously accepted the Soviet Union’s presence as a balancing factor that sustained Europe’s enduring need for American protection—a logic later institutionalized with the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in 1949. One year earlier, Washington had launched the Marshall Plan to rebuild Western Europe and bind it economically to the United States, in parallel with the Bretton Woods system, which entrenched the dollar as the world’s reserve currency and established the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank under American leadership.

Despite this substantial success in Europe, the United States did not achieve comparable results in the European colonies—particularly those of Britain and France in Africa and Asia. Washington feared that the persistence of colonial rule would enable the Soviet Union to exploit national liberation movements for strategic gain. As Nikita Khrushchev adopted a more flexible policy toward supporting such movements, the United States found itself compelled to move beyond diplomatic pressure and toward more coercive measures against its closest allies.

This approach first manifested in the Quincy Agreement between Roosevelt and King Abdulaziz Al Saud on February 14, 1945, and later in Washington’s stance toward Egypt’s July 1952 Revolution and its encouragement of agrarian reform. It reached its apex during the 1956 Suez Crisis, when the United States took a decisive stand against the tripartite aggression, employing financial and political pressure that forced Britain to withdraw and diplomatically isolated France, effectively bringing the British imperial role to an end.

France subsequently faced similar pressure over the Algerian question, as the United States refused to provide Paris with international cover for its war, encouraged a negotiated settlement, and recognized Algerian independence early—on July 3, 1962, two days before the official proclamation. This trajectory, alongside other factors, generated severe tensions in Franco–American relations, peaking in March 1966 with France’s withdrawal from NATO’s integrated military command structure—a move reversed only in 2009.

Following this “forced restructuring” of the Western system, the United States turned its attention to managing the confrontation with the Soviet Union within the framework of the Cold War—a struggle that concluded with the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact, the reunification of Germany, and Mikhail Gorbachev’s announcement of the Soviet Union’s dissolution on December 26, 1991. This marked the onset of an era of unipolarity and singular American global leadership.

Trump and the American Order: A Break in Style—or a Return to the Original?

The rules upon which the post–World War II international order was built no longer hold in the sense that originally necessitated their creation. The ideological challenge posed by communism has effectively receded with the broad acceptance of capitalism as the general framework of the global economy, even as models and degrees of application vary from one country to another. Likewise, the Soviet Union’s expansionist geopolitical challenge ended with the Soviet collapse, without being replaced by a power possessing a universalist project or a comprehensive vision of global domination. Russia and China, despite their growing international presence, do not possess a fully articulated universalist project capable of founding a coherent alternative world order, notwithstanding the general narratives they advance.

Politically, the principles that formed the “universalist” foundation of the American model after World War II—foremost among them constitutionalism, pluralistic elections, and the peaceful transfer of power—are no longer the subject of a global ideological contest as they once were. To varying degrees, these principles have become general features adopted by the overwhelming majority of states, such that international disagreement no longer centers on the legitimacy of these values as such, but rather on the mechanisms of their implementation, their practical limits, and the conditions of their fit within distinct national contexts. Outside this framework remain only a limited number of states characterized by closed systems or one-party rule, led by China, North Korea, Vietnam, Laos, Cuba, and Eritrea, as well as Afghanistan under Taliban rule.

Economically, although the dollar continues to function as the dominant international reserve currency, the instruments of American influence no longer necessarily operate through direct institutional expansion or strict adherence to multilateral organizations. Increasingly, U.S. influence is manifested in its capacity to shape and control the most consequential infrastructures of the global economic system—supply chains, the financial system, technology, energy, and innovation—even as Washington repeatedly withdraws from several international frameworks and institutions that it itself helped establish.

In the same context, capitalism—regardless of differences among national variants—has become the prevailing global economic framework, and no state now claims to possess a fully formed alternative economic system outside it. Globalization, as a dense network of interdependence, has largely achieved its major objectives: integrating markets, intensifying financial and commercial linkages, and tying national economies into a single global structure. As a result, the principle of free trade, at least in its minimal sense, has become a near-assumed value in international economic relations.

This reality, however, requires a careful distinction between two concepts that are often conflated despite their fundamental differences. The first is “free trade” in the sense of removing international commerce as a pretext for war—ending the era of sinking commercial ships, imposing comprehensive naval blockades, and forcibly closing international trade corridors. Such practices were historically treated as legitimate instruments of conflict in the classical imperial order, and they helped trigger large-scale wars, justify colonial expansion, and redraw maps by force. This meaning of free trade—understood as safeguarding freedom of navigation and preventing the militarization of global trade routes—has become part of the shared values on which the contemporary post–World War II order has rested.

The second concept is “trade liberalization,” meaning the broad and systematic removal of tariff and non-tariff barriers and the expansion of national market access for goods, capital, and foreign investment through complex institutional formulas and multilateral rules administered via international organizations and comprehensive agreements. This model—long regarded as one of the principal advantages of the U.S.-led postwar economic order, and as a mechanism for entrenching American soft economic hegemony—has gradually come to be viewed by growing segments of U.S. decision-making circles as an economic and political burden rather than a net strategic asset, especially as its costs have come to exceed its benefits and as rising powers have benefited from it without bearing its associated security or political burdens.

In this sense, the current American dilemma is no longer about free trade as a principle that ensures the flow of goods and protects maritime corridors from becoming theaters of conflict. Rather, it centers on trade liberalization as an overarching institutional choice—one increasingly seen as constraining America’s capacity for economic maneuver, for reorienting supply chains, and for deploying trade instruments as tools of strategic pressure in an international system trending toward sharper competition.

Within this context, the growing American preference for bilateral agreements over multilateral formats can be understood as a turn toward more direct instruments for maximizing returns and minimizing costs—a logic that emerged clearly in the policies of the Trump administration. This logic becomes even clearer when one considers the place of the European Union in contemporary American calculations. At its core, the European Union was established to achieve two primary aims: securing intra-European peace after centuries of war, and filling the geopolitical vacuum created by the dissolution of the Soviet Union. To a considerable degree, the Union succeeded in achieving both aims. Yet that very success has, from Washington’s perspective, made the EU a polity that no longer provides the kind of strategic added value that would justify continued American willingness to bear the costs of its protection or its institutional sponsorship, as in the past.

Accordingly, multilateral institutions and blocs created in the context of the Cold War and its aftermath are no longer viewed within the United States as indispensable tools for managing the international system. Instead, many are increasingly seen as structures whose historical functions have been exhausted and that have not been adjusted to reflect shifts in the global balance of power. From this standpoint, reducing commitments, redefining the rules of partnership, and shifting from the collective management of the system to the management of immediate interests have become central to an American repositioning in the post-classical unipolar moment.

Here the structural dilemma produced by the end of the Cold War becomes apparent. The structures and institutions the United States created to confront the Soviet Union—after displacing the European colonial legacy—were not dismantled once their mission ended. Instead, they persisted and expanded, gradually turning into a heavy bureaucratic apparatus that became a center of power in its own right, defending its gains and resisting attempts to redefine its role. Meanwhile, allies—especially the Europeans—failed to internalize the profound transformations that had reshaped the international system, continuing to treat these institutions as purely American instruments that Washington would finance, protect, and manage, without meaningful contributions that would ensure their sustainability or justify their continuation.

In addition, these institutions failed to adapt their functions and missions to the requirements of the new phase, becoming a growing fiscal burden on the U.S. Treasury without political or economic returns commensurate with their costs. Efforts to revive their relevance by mobilizing for new global struggles—whether under the banners of the “war on terror,” “democracy promotion,” or even confrontation with Russia after the war in Ukraine—did not succeed in restoring a function of genuine strategic value. Instead, these institutions continued to expand periodically without a clear purpose.

Against this backdrop, Donald Trump’s approach can be understood as a direct response to these structural imbalances. He addressed the problem by withdrawing from a number of international organizations and by shuttering U.S. institutions created for ideological purposes that had lost their rationale—such as certain media platforms once aimed at audiences in the former Soviet bloc. He also applied unprecedented pressure on allies within NATO to compel them to increase their financial and military contributions. Yet this approach, in essence, does not represent a rupture with the American tradition so much as it reflects an explicit return to foundations embedded in the political “genetics” of the American republic since its earliest formation.

The true difference, then, lies not in the objectives but in the style. Trump relied on a “shock policy,” coupled with confrontational, publicity-driven rhetoric and a deliberate departure from conventional political correctness and diplomatic decorum—reflecting the fact that he came from outside the governing establishment and did not conform to the classic political mold. Added to this is a highly consequential factor: the failure of previous administrations to address these dysfunctions in a timely manner compounded pressures on the U.S. Treasury and weakened America’s capacity to confront China, which benefited from the privileges of the post–World War II American order without bearing its burdens.

Accordingly, today’s world has come to require new rules that go beyond those that have become obsolete and incapable of addressing contemporary challenges on American terms. The mechanisms of international law and decision-making—built upon a delicate balance among the victors of World War II—have shifted from instruments of stability into constraints that bind American maneuver, while simultaneously easing the ascent of the principal competitor: China. In line with a longstanding American tradition of managing allies when they fail to respond to the requirements of a new phase—as occurred after the First and Second World Wars—Washington today, under Trump, is pursuing the same policy in a more abrasive and explicit form.

This is reflected in the evident tendency to use the “Russia card” to pressure Europe and in a less-than-strict commitment to the requirements of Article 5 of the NATO treaty—placing the European continent before a harsh equation. Either Europe assumes the full burdens of its security, a path that deepens European fragility through higher defense spending, the militarization of society, and the intensification of internal tensions—thereby opening space for the rise of far-right currents—or it accepts a recalibration of its policies in line with the new international order the United States seeks to establish.

Ultimately, Europe finds itself, in Trump’s logic, compelled to accept a new American equation—one grounded less in equitable partnership than in the redistribution of burdens within the Western camp. At its core is full European engagement in confronting China’s expanding economic influence, alongside the imposition of strict constraints on the growth of Chinese military capabilities, whether conventional or nuclear, within the frameworks and agreements inherited from the Cold War—ensuring that ultimate strategic superiority remains in American hands and preventing the emergence of an independent Chinese pole capable of acting outside the U.S.-anchored system.

This pattern of pressure is not limited to Europe alone. It is expected to be generalized gradually to other allies worldwide through reducing America’s role as a “protector” or “guarantor” of security and through a gradual retreat from bearing the costs of regional stability across vast areas. From this perspective, one can understand the clear turn in the new U.S. strategy toward concentrating on the Southern Hemisphere, alongside leaving maritime corridors and geopolitically sensitive regions without direct American security cover—and without explicit guarantees for small states against being swallowed or coerced by larger regional powers.

Nor does this relative security vacuum appear accidental or the product of an uncalculated retreat. It is more plausibly part of a deliberate strategy aimed at spreading anxiety, alarm, and uncertainty across the international system—and perhaps a measure of controlled, temporary disorder—in order to drive affected states, sooner or later, to summon the United States once again to perform its leadership role, but on different terms and within a context aligned with Washington’s new priorities. This trajectory is reinforced by the inability of different regions to build effective collective security arrangements capable of ensuring stability, providing credible deterrence, or offering reciprocal guarantees of non-aggression.

At the same time, this relative U.S. retrenchment imposes additional burdens on China by pushing it to bear the costs of protecting its expanding global trade and its supply lines stretching across seas and straits far beyond its immediate sphere—raising the costs of its economic rise and draining its strategic resources. This logic complements an accelerating American turn toward investment in Latin America, aiming to transform the region into a new low-cost industrial base—this time geographically closer to the United States and easier to regulate and control—thereby reducing reliance on Asian supply chains and re-centering industrial weight within the space proximate to Washington.

Within this framework as well, one can understand aspects of America’s demonstrative posture toward Venezuela not as a prelude to direct intervention, but rather as a deterrent signal and a deliberate effort to generate anxiety among other Latin American states—reminding them of the limits of autonomy and independence, and reasserting the American sphere of influence in the Western Hemisphere. Taken together, these moves form a preparatory context for reshaping an international order more consistent with the prevailing balance of power—one that preserves U.S. leadership and hegemony, but in a different form: fewer burdens, lighter commitments, and greater strategic and economic gains.

Accordingly, Trump’s approach does not appear as a departure from American history or a deviation from its trajectory, but rather as an explicit return to its deep foundational logic: minimizing costs, maximizing returns, and redefining alliances as functional instruments rather than permanent obligations—a logic that presents itself as the optimal path for preserving American primacy in a changing world, not by administering the old system, but by dismantling it and reconstructing it on new terms.

Conclusion

In sum, this trajectory may result in the reproduction of an older American logic in a new form: lighter commitments, a redistribution of burdens, and an instrumental approach to alliance management that ties their continuation to immediate utility within Washington’s shifting priorities. If the institutions and structures that emerged after World War II were designed to regulate the balances of a bipolar world, the Trump moment reveals an accelerating shift toward dismantling that formula—not as a forced retreat, but as an instrument for reassembling a new international order according to stricter cost-benefit calculations, and for preserving ultimate strategic superiority against competitors, foremost among them China.

The most consequential risk of this shift, however, lies in its repercussions for regional environments. The wider the relative security vacuum grows, and the more ambiguous the traditional American security umbrella becomes, the more likely it is that competition will intensify within regions themselves; that efforts at repositioning will multiply among medium and major regional powers; and that smaller states, in particular, will be pushed to seek new—or upgraded—alliances with other actors that enjoy influence in Washington. Such realignments would serve two interlocking aims: securing themselves in the near term against the risks of absorption or coercion within their regional surroundings, and ensuring a place for themselves in the shape of the new global order when the moment arrives for its American-led consolidation and its acceptance as a definitive reality.

Accordingly, the contours of the next phase will not be determined solely by the nature of the U.S.–European relationship or by how the competition with China is managed. They will also be shaped by the dynamics of alliance reconfiguration within different regions—where the ability to access circles of influence close to Washington, or to align with those who possess such access, will become among the most important determinants of survival and status. In this setting, the measured American dismantling of the old order becomes a prelude to a new global logic—one that does not reward those who wager on the stability of guarantees, but rather those who possess flexibility, adaptive capacity, and the ability to rebuild their security tools and partnerships in line with the rules the United States seeks to impose in this moment of refoundation.

Finally, the Trump administration’s pursuit of these objectives—particularly those on which it appears to converge with the governing establishment—does not necessarily imply that it will succeed in achieving them. That is a separate trajectory requiring an independent analytical study examining conditions of implementation, balances of power, constraining factors, and the limits of translating political preferences into tangible outcomes. This study, by design, has instead focused on unpacking the drivers and rationales of Trump’s policies and clarifying what he hopes to accomplish through them, without venturing into their eventual trajectories or assessing their ultimate results.